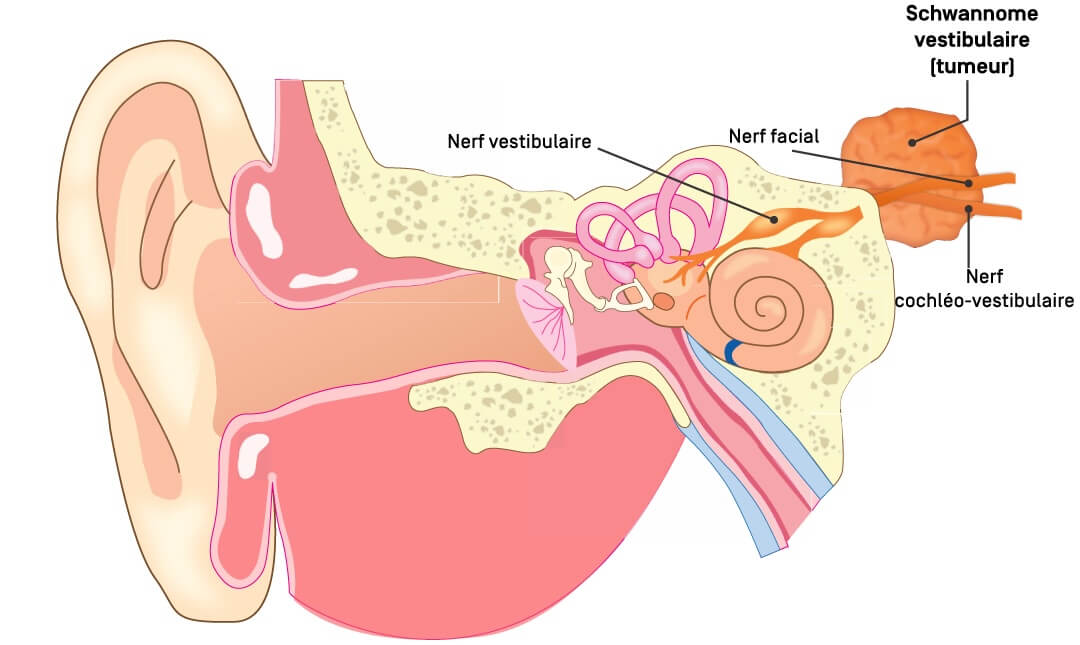

The cochlear nerve transmits sound perceptions from the cochlea to the brain, ensuring hearing. The vestibular branches, one of which is most often the starting point of the schwannoma, manage balance by relaying to the brain information from structures in the inner ear involved in the perception of movement. This tumour can therefore affect balance and hearing, leading to various auditory and neurological symptoms. Although it is not cancerous, it can cause severe complications if it grows and compresses other nearby nerves (such as the facial nerve, which runs in the internal auditory canal with the cochleovestibular branches, and also the trigeminal nerve and other cranial nerves further away) and neighbouring brain structures.

Symptoms of vestibular schwannoma

The symptoms of vestibular schwannoma appear gradually as a result of the slow growth of the tumour and compression of the nerves running through the internal auditory canal. One of the first signs is often a progressive or sudden unilateral hearing loss. This symptom is present in 60% of cases.

The other most common symptoms are

- Tinnitus: a buzzing or whistling sound in the affected ear.

- Dizziness and balance problems

In the presence of larger tumours, other symptoms may appear:

- Headaches: due to increased intracranial pressure.

- Facial numbness or weakness: if the tumour compresses adjacent nerves, such as the facial nerve or trigeminal nerve.

- Difficulty swallowing: if other surrounding cranial nerves are affected.

Causes and risk factors for vestibular schwannoma

Vestibular schwannoma is caused by an excessive proliferation of Schwann cells, which form the nerve sheath. The nerve most frequently affected is one of the vestibular branches, hence the name. The exact cause of this proliferation remains unknown in the majority of cases. The sporadic form is the most common, accounting for over 95% of vestibular schwannomas.

However, some forms are associated with a genetic mutation in the NF2 gene. This anomaly is responsible for neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2), a genetic disease in which several benign tumours, including bilateral vestibular schwannomas, affect the nervous system. Unlike sporadic forms of schwannoma, patients with NF2 often develop bilateral tumours.

Apart from this genetic disease, no clear cause has been formally identified. However, exposure to ionising radiation in childhood may be a risk factor for the development of radiation-induced tumours in general.

Diagnosing vestibular schwannoma

The diagnosis of vestibular schwannoma is based on a clinical examination, additional tests and an imaging study.

Clinical and complementary examinations

The patient is usually referred to an ENT specialist, who performs a full work-up. The first sign is often a progressive unilateral hearing loss, and an audiometric test is carried out to assess the extent of the hearing problems. Audiometry often shows an asymmetric sensorineural hearing loss, particularly marked in the high frequencies.

A brainstem auditory evoked potentials (ABR) test may be performed to assess nerve conduction. Although it is no longer routinely used, it remains a diagnostic tool in certain clinical situations and can be used as a prognostic factor for hearing conservation following treatment.

Additional vestibular examinations are also carried out. Schwannoma can damage the function of the vestibular nerve, resulting in balance disorders.

These additional examinations can be a valuable guide in the choice of treatment.

Medical imaging

The gold standard is MRI. This technique can identify very small tumours, sometimes only 1 or 2 mm in diameter. It allows precise assessment of the size of the tumour and detailed study of its anatomical relationships with adjacent structures, which is also a valuable guide in the choice of treatment.

Computed tomography (CT) is sometimes used in conjunction with MRI to assess bony changes in the internal auditory canal.

Treating vestibular schwannoma

The choice of treatment depends on a number of factors, including the size of the tumour, the presence and type of symptoms and the patient's general condition. There are three main options:

1. Active surveillance

As vestibular schwannoma is a benign, slow-growing tumour, simple surveillance may be recommended when the tumour is small and does not cause significant symptoms.

Patients undergoing active surveillance receive ENT and MRI follow-up (usually annually) to assess tumour progression and its possible impact on hearing or other symptoms.

The aim of active surveillance is to determine the right time for proactive management, in particular radiosurgery, since in the long term this approach offers better functional results, particularly in terms of hearing conservation, than continued surveillance for progressive tumours.

2. Radiosurgery / Stereotactic radiotherapy

Stereotactic radiosurgery is a non-invasive treatment option. This single-session radiotherapy technique delivers a high dose of targeted radiation with millimetre precision. It is based on the use of a three-dimensional guidance system that enables the tumour to be reached without incision and its growth to be stopped. Stereotactic radiosurgery is particularly indicated for small to medium-sized vestibular schwannomas (generally less than 3 cm), when the tumour is not yet causing cerebral compression. This technique is an effective alternative to surgery, and is currently the first choice of treatment, with significantly fewer risks and a better chance of preserving function, particularly hearing.

The recommended dose is generally 12 Gy (11 to 13 Gy, depending on the team, the equipment used and the size of the tumour), which makes it possible to achieve a tumour control rate (i.e. absence of growth) of over 95% for more than 10 years, while allowing a high rate of preservation of hearing and other nerve functions.

In some cases, hypofractionated radiosurgery (or fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy) may be recommended. This technique divides the total radiation dose into several sessions (generally 3 to 5) and is used in particular when the tumour is larger, close to sensitive structures such as the brain stem, and the patient cannot benefit from surgery.

3. Surgery

When the tumour reaches a significant size or causes severe symptoms due to compression of certain brain structures, surgery is often the preferred treatment option.

Surgery may be recommended in a number of specific situations:

When the tumour is large (generally more than 3 cm) and is compressing the brain stem, and may also be associated with intracranial hypertension or hydrocephalus.

When non-invasive treatments (radiosurgery) have failed, or when tumour growth is rapid and uncontrolled, and histological analysis of the tumour is necessary (diagnostic doubt)

The operation is adapted to the size and location of the tumour and the functional status of the hearing and facial nerve. Three main surgical approaches are used:

- Retrosigmoid or suboccipital approach: this is the surgical approach most often used. It is indicated for medium-sized tumours in which an attempt can be made to preserve hearing, provided that the tumour is not too invasive. It is also recommended for large tumours, particularly in the ‘combined approach’ of partial resection followed by radiosurgery, which provides very good functional results and significantly reduces the risk of sequelae.

- Translabyrinthine approach: preferred when it is no longer possible to preserve hearing. It involves passing through the bone of the labyrinth (structure of the inner ear), allowing excellent visual control of the tumour and surrounding cranial nerves. It is often preferred for large tumours and ensures complete resection while reducing the risk of recurrence. However, it does result in permanent hearing loss on the operated side.

- Suprapetrous approach (middle fossa): indicated for small tumours located exclusively in the internal auditory canal (intracanal). It allows access to the tumour through an opening in the temporal bone and allows better preservation of hearing where this is still possible.

However, surgery is associated with complications such as facial weakness, total hearing loss and an increased risk of cerebrospinal fluid leakage and infection.

Nowadays, only the largest tumours, which cause compression and a mass effect on cerebral structures, require surgical removal. For smaller tumours, the radiosurgery approach, which “blocks” the growth of the tumour, is preferred, as it offers much better functional results and fewer risks of complications. In addition, in the case of large tumours requiring surgery, it is now possible to offer an approach combining partial excision surgery (reduction of the volume by removing the tumour via the retro-sigmoid route, without affecting the nerves on its surface) followed by radiosurgery on the tumour residue to prevent further progression. This approach produces functional results for the facial nerve and hearing that are very close to those obtained with radiosurgery alone on smaller tumours.

Progression and possible complications

Vestibular schwannoma is a benign tumour that generally progresses slowly. In most cases, the situation remains clinically stable and does not require urgent intervention. This is why active surveillance is sometimes the first choice, with regular ENT and MRI scans to detect any progression. When treatment is required, modern approaches such as stereotactic radiosurgery or fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy can stop tumour growth in over 95% of cases, while offering the best chance of preserving hearing and nerve function. Potential complications vary depending on the treatment chosen. After surgery, patients may experience facial weakness, trigeminal nerve damage leading to pain or numbness, and complete hearing loss. Radiosurgery and FSRT, although less invasive, still present a certain percentage risk of hearing deterioration and balance problems. However, in patients who still have good hearing at the time of treatment, radiosurgery offers the best chance of preserving hearing in the long term.

As the tumour grows, it can lead to complications when it reaches a significant size. If left untreated, tumour growth can lead to irreversible hearing loss, impaired balance, compression of adjacent cranial nerves and, in rare cases, compression of the brainstem, leading to serious neurological complications, hydrocephalus and intracranial hypertension.

Preventing vestibular schwannoma

To date, there are no effective preventive measures to avoid the development of sporadic vestibular schwannoma. As the exact causes of this benign tumour are still poorly understood, it is not possible to identify modifiable risk factors to prevent its development. In the absence of prevention, early diagnosis remains one of the best ways of avoiding complications associated with the tumour's development.

When should you contact the Doctor?

It is advisable to consult a doctor as soon as unusual symptoms appear, in particular hearing loss in one ear only, persistent tinnitus or unexplained vertigo. These signs may indicate the presence of a vestibular schwannoma and require an ENT examination and in-depth tests to establish a precise diagnosis.

Care at Hôpital de La Tour

Hôpital de La Tour offers comprehensive, multidisciplinary treatment for vestibular schwannoma, bringing together specialists in otorhinolaryngology (ENT), neurosurgery and radiotherapy. Thanks to its expertise and cutting-edge equipment, the centre offers personalised treatment, tailored to each patient according to the progress of the tumour, symptoms and therapeutic expectations.

The ENT Centre at Hôpital de La Tour brings together a number of specialists with experience in diagnosing and treating auditory and vestibular pathologies.

Hôpital de La Tour has the NeuroKnife centre, which specializes in high-precision radio-neurosurgery (stereotactic radiosurgery of the nervous system), notably incorporating advanced Varian Edge technology, which enables vestibular schwannomas to be treated optimally by first-line radiosurgery. This technique enables the tumour to be targeted with millimetre precision, and is also offered to patients who cannot be operated on, or for whom a combined approach of surgery and radiosurgery is chosen.

When surgery is required, close collaboration between ENT specialists and neurosurgeons helps to optimise the choice of technique and improve the preservation of hearing and facial function. The ENT centre's expertise also extends to post-treatment follow-up, with auditory and vestibular re-education to help patients regain optimal balance after surgery.

FAQ sur le schwannome vestibulaire

Is a vestibular schwannoma or acoustic neuroma a malignant tumour?

No, it is a benign tumour, which means that it does not spread to other parts of the body. However, it can cause local complications if it grows.

Can a vestibular schwannoma be prevented?

There is no effective prevention. Certain genetic diseases such as neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2) increase the risk. Medical monitoring is recommended for people with a family history.

What treatments are available at Hôpital de La Tour?

Options include active surveillance, ENT and neurosurgical procedures and non-invasive treatments using stereotactic radiosurgery (NeuroKnife Centre).

What is the follow-up after treatment?

Regular medical follow-up is necessary, including follow-up MRI scans, hearing tests and, if necessary, vestibular rehabilitation to improve the patient's balance and adaptation.